Definition

The stock market crash of 1929 was a massive crash in stock prices on the New York Stock Exchange, and marks the largest financial crash in the United States.

Details

The stock market crash came in multiple parts – the initial crash on October 28 (a 12.87% drop) continued into October 29 (a 11.73% drop), but prices continued to decline until 1932, with a total loss of 89%. The crash marked the start of, and is one of the major causes of, the Great Depression.

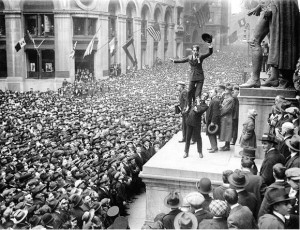

Initially, some of the most wealthy bankers and industrialists tried to halt the crash by buying up millions of dollars in stocks themselves to try to boost prices. On the first day of the crash, the heads of several of the biggest banks in New York pooled their resources to buy huge amounts of US Steel (Stock Symbol: [hq]X[/hq]) and other Blue Chip stocks. After this gesture, the panic began to subside and prices stopped dropping for the day.

However, the next morning prices resumed their fall, and further huge purchases by the Rockefeller family, and many others, were unable to restore investor confidence. Many people had been using stocks as collateral for loans they had taken out at banks – when the stock value dropped, the banks would often ask people and businesses to repay their loans, causing a massive wave of bankruptcies. This is how the crash in stock prices spread to the economy as a whole.

Causes Of The Stock Market Crash

There are several main causes of the 1929 stock market crash, ranging from wheat farmers through investment bankers and all points in between.

Millions Of New Investors Entering The Market

After World War One, millions of Americans began moving to the cities looking for work, and a new middle class began to emerge from the prosperity that followed the end of the war. This new group of people wanted effective ways to save their money and secure a more profitable return than simply keeping it in a savings account. Generally speaking, they chose to invest in stocks.

Today, this would not be much of an issue, but before the 20th century most investing was in bonds. The transition to stock trading came about because of railroad companies and new industrial companies. This new middle class was also buying cars and houses, which was good for business for steel and construction companies. This made their stock price rise.

This was the first time that small investors were buying stocks in a large scale (before the 1920’s, buying stocks was usually done only by the wealthy), and they generally were buying companies that they already saw the prices rising for to try to secure the highest return. The average P/E ratio (the stock’s price divided by its earnings – per – share) of the most popular stocks was extremely high compared to what is normally seen today.

When the stock market crash started, it knocked most of these new investors out of the market completely – they were forced to sell their shares and lost all of their savings. This meant that there were fewer investors available to buy stocks and help start a recovery.

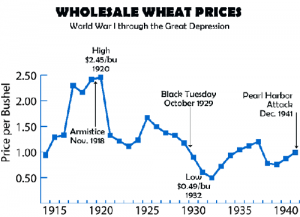

Crash In Wheat Prices

The year before the stock market crash, American farmers produced record amounts of wheat, so much that it was not all sold by the end of the year. In 1929, wheat prices started to fall as the suppliers were struggling to sell off their reserves as the new harvests came in. Countries like France and Italy were also having huge harvests, so it was not possible to get rid of the extra supply by exporting it, but in 1929 the American harvest was also lower than the previous year.

This meant that farmers who were already facing very low prices now also had less wheat to sell, which caused many farms to fail. Back at this time, a large amount of the US economy was still based on agriculture – from industrial companies selling tractors and farm equipment, to railroads shipping grain from the farms to the cities and ports, to investors trading futures in wheat. When the farms started to fail, it caused a ripple effect through many other sectors through the Summer of 1929, which made investors already very nervous by the time of the October stock market crash.

Trading On Margin

The 1920’s, leading up to the stock crash, also featured a huge amount of margin trading – when investors borrow money using stock as collateral, and use the loan to buy even more stock. Since stock prices were rising constantly, banks were happy to give the loans and investors, both new and old, were taking them and turning huge profits. So long as the profit made on the stock is greater than the interest paid on the loan, it seemed like a good idea to keep borrowing money.

However, if the stock prices start to fall when you are trading on margin, you end up both losing your investment and having to pay back the loan – with interest. Once stocks started to lose value at the start of the crash, many lenders started to fear that borrowers would lose too much value and not pay back their loans, so they “called” the loans. This meant they made investors pay back the loan amount immediately. This meant that many investors who had traded on margin were forced to sell off their stocks to pay back their loans – when millions of people were trying to sell stocks at the same time with very few buyers, it caused the prices to fall even more, leading to a bigger stock market crash.

For investors, if their stocks fell more than 50%, they would have to pay back more than the total amount they had invested. This happened frequently, causing many individuals, and lenders they were supposed to pay back, to lose their entire investments plus extra. Since they owed money with the stocks as collateral, they could not even hold the stocks and hope the value would recover – the lenders became the owners of the stock when the borrower could not pay back, and the lenders again tried to sell the stocks immediately to make up some of their losses.

Speculation

The biggest cause of the stock market crash was speculation. As prices began to rise for stocks, more investors wanted to buy to make sure they did not “miss out” on great investments. Both new and old investors saw 20%+ returns on their investments through the 1920’s, which is what drew so many new investors to put all their savings into stocks. At the same time, more and more people were trading on margin to take advantage of the rising prices and get even more profits.

This meant that as the stock prices started rising, more people were demanding more stock, which caused the price to rise even more. This is called a “speculative bubble”, and as more people were trading with more borrowed money, it began to become very unstable.

In 1929, industrial production started to slow down, with slightly less steel, cars, and houses built than the years before. This, along with the shock caused by the fall in wheat prices, finally caused some stocks to start to lose value. As soon as some investors started to lose value, many others tried to sell their stocks as quickly as possible to avoid more losses, which multiplied the problem.

Information

One of the biggest reasons the problems were able to get as bad as they did, and the panic was able to spread so quickly, was a lack of information. New investors were not fully aware of the risks they were making when they began investing (nobody let them practice trading on HowTheMarketWorks!), and the economy was evolving so quickly that even professional investors did not know if prices were rising because of a general increase in value, or as part of a bubble.

During the crash itself, so many people were trading in such high volumes that the stock tickers were not able to keep up – often falling 3 or more hours behind the real-time prices. Since investors did not know how much they were losing, but they knew things were bad, it caused even more panic and more people pushing to sell everything as fast as possible. One minor result of the stock crash was a huge improvement to the ticker system to speed up how fast information could be conveyed to investors.

MGH_InvestmentTrader_Business

MGH_InvestmentTrader_Business Insurance

Insurance